Abstract

Depressive disorders are among the leading causes of global disease burden, but there has been limited progress in understanding the causes of and treatments for these disorders. In this Perspective, we suggest that such progress depends crucially on our ability to measure depression. We review the many problems with depression measurement, including the limited evidence of validity and reliability. These issues raise grave concerns about common uses of depression measures, such as for diagnosis or tracking treatment progress. We argue that shortcomings arise because the measurement of depression rests on shaky methodological and theoretical foundations. Moving forward, we need to break with the field’s tradition, which has, for decades, divorced theories about depression from how we measure it. Instead, we suggest that epistemic iteration, an iterative exchange between theory and measurement, provides a crucial avenue for progressing how we measure depression.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$59.00 per year

only $4.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

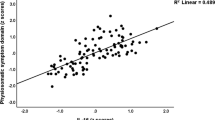

Data underlying Figs 1,2 and 3 can be found at https://osf.io/7dp5s/.

Code availability

Code to reproduce Figs 1 and 2 (minus graphical edits performed by the journal art editor), and run the simulation underlying Fig. 3, can be found at https://osf.io/7dp5s/.

References

Santor, D. A., Gregus, M. & Welch, A. Eight decades of measurement in depression. Measurement 4, 135–155 (2006).

van Noorden, R., Maher, B. & Nuzzo, R. The top 100 papers. Nature 514, 550–553 (2014).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23, 56–62 (1960).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571 (1961).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Jorm, A. F., Patten, S. B., Brugha, T. S. & Mojtabi, R. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 16, 90–99 (2017).

Kapur, S., Phillips, A. G. & Insel, T. Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Mol. Psychiatry 17, 1174–1179 (2012).

Scull, A. American psychiatry in the new millennium: a critical appraisal. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001975 (2021).

Cuijpers, P. et al. The effects of psychotherapies for depression on response, remission, reliable change, and deterioration: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 144, 288–299 (2021).

Khan, A. & Brown, W. A. Antidepressants versus placebo in major depression: an overview. World Psychiatry 14, 294–300 (2015).

Kendler, K., Munõz, R. & Murphy, G. The development of the Feighner criteria: a historical perspective. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 134–142 (2010).

Spitzer, R. L. Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr. Psychiatry 24, 399–411 (1983).

Horwitz, A. V. in The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology (eds Cautin, R. L. & Lilienfeld, S. O.) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp012 (Wiley, 2015).

Beck, A. Reliability of psychiatric diagnoses: 1. A critique of systematic studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 119, 210–216 (1962).

Ash, P. The reliability of psychiatric diagnoses. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 44, 272–276 (1949).

Feighner, J. P. et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 26, 57–63 (1972).

APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 3rd edn (American Psychiatric Association, 1980).

Fried, E. The 52 symptoms of major depression: lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. J. Affect. Disord. 208, 191–197 (2017).

Cipriani, A. et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 391, 1357–1366 (2018).

Cronbach, L. J. & Meehl, P. E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol. Bull. 52, 281–302 (1955).

Robins, E. & Guze, S. B. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 126, 983–987 (1970).

Bandalos, D. L. Measurement Theory and Applications for the Social Sciences (Guilford, 2018).

Kane, M. T. Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. J. Educ. Meas. 50, 1–73 (2013).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 737–745 (2010).

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, 2014).

Messick, S. Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educ. Res. 18, 5–11 (1989).

Fried, E. I. Corrigendum to “The 52 symptoms of major depression: lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales” [Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 191–197]. J. Affect. Disord. 260, 744 (2020).

Mew, E. J. et al. Systematic scoping review identifies heterogeneity in outcomes measured in adolescent depression clinical trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 126, 71–79 (2020).

Chevance, A. M. et al. Identifying outcomes for depression that matter to patients, informal caregivers and healthcare professionals: qualitative content analysis of a large international online survey. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 692–702 (2020).

Wittkampf, K. et al. The accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in detecting depression and measuring depression severity in high-risk groups in primary care. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 31, 451–459 (2009).

Sayer, N. N. A. et al. The relations between observer-rating and self-report of depressive symptomatology. Psychol. Assess. 5, 350–360 (1993).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. Translating the BDI and BDI-II into the HAMD and vice versa with equipercentile linking. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, E24 (2019).

Fried, E. et al. Measuring depression over time … or not? Lack of unidimensionality and longitudinal measurement invariance in four common rating scales of depression. Psychol. Assess. 28, 1354–1367 (2016).

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, F. S. & Emery, G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression (Guilford, 1979).

Montgomery, S. A. & Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 134, 382–389 (1979).

von Glischinski, M., von Brachel, R., Thiele, C. & Hirschfeld, G. Not sad enough for a depression trial? A systematic review of depression measures and cut points in clinical trial registrations: systematic review of depression measures and cut points. J. Affect. Disord. 292, 36–44 (2021).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613 (2001).

Levis, B. et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 122, 115–128.e1 (2020).

Whiston, S. Principles and Applications of Assessment in Counseling (Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning, 2009).

Thombs, B. D., Kwakkenbos, L., Levis, A. W. & Benedetti, A. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 190, 44–49 (2018).

Lavender, J. M. & Anderson, D. A. Effect of perceived anonymity in assessments of eating disordered behaviors and attitudes. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 42, 546–551 (2009).

Keel, P. K., Crow, S., Davis, T. L. & Mitchell, J. E. Assessment of eating disorders: comparison of interview and questionnaire data from a long-term follow-up study of bulimia nervosa. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 1043–1047 (2002).

Croskerry, P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad. Med. 78, 775–780 (2003).

Kim, N. S. & Ahn, W. Clinical psychologists’ theory-based representations of mental disorders predict their diagnostic reasoning and memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 131, 451–476 (2002).

Aboraya, A. Clinicians’ opinions on the reliability of psychiatric diagnoses in clinical settings. Psychiatry 4, 31–33 (2007).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Ruscio, J., Zimmerman, M., McGlinchey, J. B., Chelminski, I. & Young, D. Diagnosing major depressive disorder XI: a taxometric investigation of the structure underlying DSM-IV symptoms. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 195, 10–19 (2007).

Haslam, N. Categorical versus dimensional models of mental disorder: the taxometric evidence. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 37, 696–704 (2003).

Haslam, N., Holland, E. & Kuppens, P. Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: a quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychol. Med. 42, 903–920 (2012).

Nettle, D. in Maladapting Minds: Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Evolutionary Theory (eds Adriaens, P. R. & De Block, A.) 192–209 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Courtney, D. B. et al. Forks in the road: definitions of response, remission, recovery and other dichotomized outcomes in randomized controlled trials for adolescent depression. A scoping review. Depress. Anxiety 38, 1152–1168 (2021).

Fried, E. & Nesse, R. M. Depression sum-scores don’t add up: why analyzing specific depression symptoms is essential. BMC Med. 13, 1–11 (2015).

McNeish, D. & Wolf, M. G. Thinking twice about sum scores. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 2287–2305 (2020).

Gullion, C. M. & Rush, A. J. Toward a generalizable model of symptoms in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 44, 959–972 (1998).

Helmes, E. & Nielson, W. R. An examination of the internal structure of the Center for Studies-Depression Scale in two medical samples. Pers. Individ. Dif. 25, 735–743 (1998).

Shafer, A. B. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. J. Clin. Psychol. 62, 123–146 (2006).

van Loo, H. M., de Jonge, P., Romeijn, J.-W., Kessler, R. C. & Schoevers, R. A. Data-driven subtypes of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. BMC Med. 10, 156 (2012).

Quilty, L. C. et al. The structure of the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale over the course of treatment for depression. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 175–184 (2013).

Elhai, J. D. et al. The factor structure of major depression symptoms: a test of four competing models using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Psychiatry Res. 199, 169–173 (2012).

Wardenaar, K. J. et al. The structure and dimensionality of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self Report (IDS-SR) in patients with depressive disorders and healthy controls. J. Affect. Disord. 125, 146–154 (2010).

Wood, A. M., Taylor, P. J. & Joseph, S. Does the CES-D measure a continuum from depression to happiness? Comparing substantive and artifactual models. Psychiatry Res. 177, 120–123 (2010).

Furukawa, T. et al. Cross-cultural equivalence in depression assessment: Japan–Europe–North American study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 112, 279–285 (2005).

Lux, V. & Kendler, K. Deconstructing major depression: a validation study of the DSM-IV symptomatic criteria. Psychol. Med. 40, 1679–1690 (2010).

Fried, E., Nesse, R. M., Zivin, K., Guille, C. & Sen, S. Depression is more than the sum score of its parts: individual DSM symptoms have different risk factors. Psychol. Med. 44, 2067–2076 (2014).

Faravelli, C., Servi, P., Arends, J. & Strik, W. Number of symptoms, quantification, and qualification of depression. Compr. Psychiatry 37, 307–315 (1996).

Tweed, D. L. Depression-related impairment: estimating concurrent and lingering effects. Psychol. Med. 23, 373–386 (1993).

Fried, E. & Nesse, R. M. The impact of individual depressive symptoms on impairment of psychosocial functioning. PLoS ONE 9, e90311 (2014).

Hasler, G., Drevets, W. C., Manji, H. K. & Charney, D. S. Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1765–1781 (2004).

Myung, W. et al. Genetic association study of individual symptoms in depression. Psychiatry Res. 198, 400–406 (2012).

Kendler, K., Aggen, S. H. & Neale, M. C. Evidence for multiple genetic factors underlying DSM-IV criteria for major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 70, 599–607 (2013).

Nagel, M., Watanabe, K., Stringer, S., Posthuma, D. & Van Der Sluis, S. Item-level analyses reveal genetic heterogeneity in neuroticism. Nat. Commun. 9, 905 (2018).

Hilland, E. et al. Exploring the links between specific depression symptoms and brain structure: a network study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74, 220–221 (2020).

Fried, E. et al. Using network analysis to examine links between individual depressive symptoms, inflammatory markers, and covariates. Psychol. Med. 50, 2682–2690 (2020).

Eeden, W. A. V. et al. Basal and LPS-stimulated inflammatory markers and the course of individual symptoms of depression. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 235 (2020).

Keller, M. C. & Nesse, R. M. Is low mood an adaptation? Evidence for subtypes with symptoms that match precipitants. J. Affect. Disord. 86, 27–35 (2005).

Keller, M. C. & Nesse, R. M. The evolutionary significance of depressive symptoms: different adverse situations lead to different depressive symptom patterns. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 316–330 (2006).

Keller, M. C., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1521–1529 (2007).

Cramer, A. O. J., Borsboom, D., Aggen, S. H. & Kendler, K. The pathoplasticity of dysphoric episodes: differential impact of stressful life events on the pattern of depressive symptom inter-correlations. Psychol. Med. 42, 957–965 (2013).

Fried, E. et al. From loss to loneliness: the relationship between bereavement and depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 124, 256–265 (2015).

Rush, A. J., Gullion, C. M., Basco, M. R., Jarrett, R. B. & Trivedi, M. H. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol. Med. 26, 477–486 (1996).

Rush, A. J. et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major dDepression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 573–583 (2003).

Fried, E. & Nesse, R. M. Depression is not a consistent syndrome: an investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. J. Affect. Disord. 172, 96–102 (2015).

Zimmerman, M., Ellison, W., Young, D., Chelminski, I. & Dalrymple, K. How many different ways do patients meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder? Compr. Psychiatry 56, 29–34 (2014).

Lichtenberg, P. & Belmaker, R. H. Subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 79, 131–135 (2010).

Baumeister, H. & Parker, J. D. Meta-review of depressive subtyping models. J. Affect. Disord. 139, 126–140 (2012).

Bech, P. Struggle for subtypes in primary and secondary depression and their mode-specific treatment or healing. Psychother. Psychosom. 79, 331–338 (2010).

Lam, R. W. & Stewart, J. N. The validity of atypical depression in DSM-IV. Compr. Psychiatry 37, 375–383 (1996).

Davidson, J. R. T. A history of the concept of atypical depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 10–15 (2007).

Arnow, B. A. et al. Depression subtypes in predicting antidepressant response: a report from the iSPOT-D trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 172, 743–750 (2015).

Paykel, E. S. Basic concepts of depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 10, 279–289 (2008).

Rush, A. J. The varied clinical presentations of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 4–10 (2007).

Melartin, T. et al. Co-morbidity and stability of melancholic features in DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 34, 1443 (2004).

Fried, E., Coomans, F. & Lorenzo-luaces, L. The 341 737 ways of qualifying for the melancholic specifier. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 479–480 (2020).

Oquendo, M. A. et al. Instability of symptoms in recurrent major depression: a prospective study. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 255–261 (2004).

Coryell, W. et al. Recurrently situational (reactive) depression: a study of course, phenomenology and familial psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 31, 203–210 (1994).

Pae, C. U., Tharwani, H., Marks, D. M., Masand, P. S. & Patkar, A. A. Atypical depression: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs 23, 1023–1037 (2009).

Magnusson, A. & Boivin, D. Seasonal affective disorder: an overview. Chronobiol. Int. 20, 189–207 (2003).

Meyerhoff, J., Young, M. A. & Rohan, K. J. Patterns of depressive symptom remission during the treatment of seasonal affective disorder with cognitive-behavioral therapy or light therapy. Depress. Anxiety 35, 457–467 (2018).

Lam, R. W. et al. Efficacy of bright light treatment, fluoxetine, and the combination in patients with nonseasonal major depressive disorder a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 56–63 (2016).

Meredith, W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika 58, 525–543 (1993).

Kendler, K. et al. The similarity of the structure of DSM-IV criteria for major depression in depressed women from China, the United States and Europe. Psychol. Med. 45, 1945–1954 (2015).

Yu, X., Tam, W. W. S., Wong, P. T. K., Lam, T. H. & Stewart, S. M. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr. Psychiatry 53, 95–102 (2012).

Nguyen, H. T., Kitner-Triolo, M., Evans, M. K. & Zonderman, A. B. Factorial invariance of the CES-D in low socioeconomic status African Americans compared with a nationally representative sample. Psychiatry Res. 126, 177–187 (2004).

Crockett, L. J., Randall, B. A., Shen, Y.-L., Russell, S. T. & Driscoll, A. K. Measurement equivalence of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: a national study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 47–58 (2005).

Baas, K. D. et al. Measurement invariance with respect to ethnicity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). J. Affect. Disord. 129, 229–235 (2011).

Williams, C. D. et al. CES-D four-factor structure is confirmed, but not invariant, in a large cohort of African American women. Psychiatry Res. 150, 173–180 (2007).

Stochl, J. et al. On dimensionality, measurement invariance, and suitability of sum scores for the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7. Assessment 29, 355–366 (2022).

Fokkema, M., Smits, N., Kelderman, H. & Cuijpers, P. Response shifts in mental health interventions: an illustration of longitudinal measurement invariance. Psychol. Assess. 25, 520–531 (2013).

Bagby, R. M., Ryder, A. G., Schuller, D. R. & Marshall, M. B. Reviews and overviews the hamilton depression rating scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am. J. Psyc 161, 2163–2177 (2004).

Trajković, G. et al. Reliability of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a meta-analysis over a period of 49 years. Psychiatry Res. 189, 1–9 (2011).

Regier, D. A. et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, part II: test–retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 59–70 (2013).

Bruchmüller, K., Margraf, J., Suppiger, A. & Schneider, S. Popular or unpopular? Therapists’ use of structured interviews and their estimation of patient acceptance. Behav. Ther. 42, 634–643 (2011).

Kupfer, D. J. & Kraemer, H. C. Field trial results guide DSM recommendations. Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-j-kupfer-md/dsm-5_b_2083092.html (2013).

Clarke, D. E. et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, part I: study design, sampling strategy, implementation, and analytic approaches. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 43–58 (2012).

Fernández, A. et al. Is major depression adequately diagnosed and treated by general practitioners? Results from an epidemiological study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 32, 201–209 (2010).

Huxley, P. Mental illness in the community: the Goldberg–Huxley model of the pathway to psychiatric care. Nord. J. Psychiatry, Suppl. 50, 47–53 (1996).

Flake, J. K., Pek, J. & Hehman, E. Construct validation in social and personality research: current practice and recommendations. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8, 370–378 (2017).

de Vet, H. C. W., Terwee, C. B., Mokkink, L. B. & Knol, D. L. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R. & Ranieri, W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 67, 588–597 (1996).

McPherson, S. & Armstrong, D. Psychometric origins of depression. Hist. Hum. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/09526951211009085 (2021).

Lilienfeld, S. O. DSM-5: centripetal scientific and centrifugal. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 21, 269–279 (2014).

Flake, J. K. & Fried, E. Measurement schmeasurement: questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 3, 456–465 (2020).

Robinaugh, D. J., Haslbeck, J. M. B., Ryan, O., Fried, E. & Waldorp, L. J. Invisible hands and fine calipers: a call to use formal theory as a toolkit for theory construction. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 725–743 (2021).

Robinaugh, D. J. et al. Advancing the network theory of mental disorders: a computational model of panic disorder. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/km37w (2019).

Fried, E. Lack of theory building and testing impedes progress in the factor and network. Psychol. Inq. 31, 271–288 (2020).

Van Bork, R., Wijsen, L. D. & Rhemtulla, M. Toward a causal interpretation of the common factor model. Disputatio 9, 581–601 (2017).

Fried, E. Problematic assumptions have slowed down depression research: why symptoms, not syndromes are the way forward. Front. Psychol. 6, 1–11 (2015).

Fried, E. & Cramer, A. O. J. Moving forward: challenges and directions for psychopathological network theory and methodology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 999–1020 (2017).

Fried, E. Moving forward: how depression heterogeneity hinders progress in treatment and research. Expert Rev. Neurother. 17, 423–425 (2017).

Fried, E. & Robinaugh, D. J. Systems all the way down: embracing complexity in mental health research. BMC Med. 18, 1–4 (2020).

Cicchetti, D. & Rogosch, F. A. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 8, 597–600 (1996).

Borsboom, D. et al. Kinds versus continua: a review of psychometric approaches to uncover the structure of psychiatric constructs. Psychol. Med. 46, 1567–1579 (2016).

Chang, H. Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

Borsboom, D., van der Maas, H. L. J., Dalege, J., Kievit, R. & Haig, B. Theory construction methodology: a practical framework for theory formation in psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 756–766 (2020).

Borsboom, D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 16, 5–13 (2017).

Kendler, K., Zachar, P. & Craver, C. What kinds of things are psychiatric disorders? Psychol. Med. 41, 1143–1150 (2011).

Olthof, M., Hasselman, F., Maatman, F. O. & Bosman, A. M. T. Complexity theory of psychopathology. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/f68ej (2021).

Robinaugh, D. J., Hoekstra, R. H. A., Toner, E. R. & Borsboom, D. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol. Med. 50, 353–366 (2020).

Hammen, C. Stress and depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1, 293–319 (2005).

Kendler, K., Karkowski, L. M. & Prescott, C. A. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 156, 837–841 (1999).

Mazure, C. M. Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 5, 291–313 (1998).

McKnight, P. E. & Kashdan, T. B. The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 243–259 (2009).

Brouwer, M. E. et al. Psychological theories of depressive relapse and recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 74, 101773 (2019).

Myin-Germeys, I. & Kuppens, P. The Open Handbook of Experience Sampling Methodology: A Step-by-step Guide to Designing, Conducting, and Analyzing ESM Studies (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2021).

Zung, W. W. K. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 12, 63–70 (1965).

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W. & Swinson, R. P. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 10, 176–181 (1998).

Sijtsma, K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of cronbach. Psychometrika 74, 107–120 (2009).

Smaldino, P. in Computational Social Psychology (eds Vallacher, R. B., Read, S. J. & Nowak, A.) (Taylor & Francis, 2017).

Presser, S. et al. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opin. Q. 68, 109–130 (2004).

Gordon Wolf, M., Ihm, E., Maul, A. & Taves, A. Survey item validation. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/k27w3 (2019).

Hawkes, N. & Brown, G. in Assessment in Cognitive Therapy (eds Brown, G. & Clark, D.) 243–267 (Guilford, 2015).

Willis, G. B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design (Sage, 2004).

Brown, G., Hawkes, N. & Tata, P. Construct validity and vulnerability to anxiety: a cognitive interviewing study of the revised Anxiety Sensitivity Index. J. Anxiety Disord. 23, 942–949 (2009).

Patalay, P. & Fried, E. Editorial Perspective: Prescribing measures: unintended negative consequences of mandating standardized mental health measurement. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 8, 1032–1036 (2021).

Neumann, L. Transparency in Measurement: Reviewing 100 Empirical Papers Using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Leiden Univ., 2020).

Williams, J. B. W. Standardizing the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: past, present, and future. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 251, 6–12 (2001).

Cybulski, L., Mayo-Wilson, E., Grant, S., Corporation, R. & Monica, S. Improving transparency and reproducibility through registration: the status of intervention trials published in clinical psychology journals. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 84, 753–767 (2016).

Ramagopalan, S. V. et al. Prevalence of primary outcome changes in clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 3, 77 (2018).

Monsour, A. et al. Primary outcome reporting in adolescent depression clinical trials needs standardization. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20, 1–15 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M.G. Wolf, N. Butcher and Z. Cohen for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. E.I.F. is supported by funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant no. 949059). D.J.R. was supported by funding from the National Institute for Mental Health (K23 MH113805). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.I.F and D.J.R. developed the idea and outline for the manuscript, E.I.F. and D.J.R. conducted background research for the manuscript and all authors contributed to writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Ioana Cristea, Kenneth Kendler and Suneeta Monga for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fried, E.I., Flake, J.K. & Robinaugh, D.J. Revisiting the theoretical and methodological foundations of depression measurement. Nat Rev Psychol 1, 358–368 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00050-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00050-2

This article is cited by

-

Designing and evaluating tasks to measure individual differences in experimental psychology: a tutorial

Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications (2024)

-

Elevating the field for applying neuroimaging to individual patients in psychiatry

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

Genetic similarity between relatives provides evidence on the presence and history of assortative mating

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Ein offenes transtheoretisches Therapie- und Trainingsmodell (4TM)

Die Psychotherapie (2024)

-

The impact of an unstable job on mental health: the critical role of self-efficacy in artificial intelligence use

Current Psychology (2024)