Abstract

Introduction

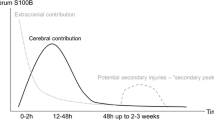

Patients suffering from severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) often develop secondary brain lesions that may worsen outcome. S100B, a biomarker of brain damage, has been shown to increase in response to secondary cerebral deterioration. The aim of this study was to analyze the occurrence of secondary increases in serum levels of S100B and their relation to potential subsequent radiological pathology present on CT/MRI-scans.

Methods

Retrospective study from a trauma level 1 hospital, neuro-intensive care unit. 250 patients suffering from TBI were included. Inclusion required a minimum of two radiological examinations and at least three serum samples of S100B, with at least one >48 h after trauma.

Results

Secondary pathological findings on CT/MRI, present in 39 % (n = 98) of the patients, were highly correlated to secondary increases of ≥0.05 μg/L S100B (P < 0.0001, pseudo-R 2 0.532). Significance remained also after adjusting for known important TBI predictors. In addition, secondary radiological findings were significantly correlated to outcome (Glasgow Outcome Score, GOS) in uni-(P < 0.0001, pseudo-R 2 0.111) and multivariate analysis. The sensitivity and specificity of detecting later secondary radiological findings was investigated at three S100B cut-off levels: 0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 μg/L. A secondary increase of ≥0.05 μg/L had higher sensitivity (80 %) but lower specificity (89 %), compared with a secondary increase of ≥0.5 μg/L (16 % sensitivity, 98 % specificity), to detect secondary radiological findings.

Conclusions

Secondary increases in serum levels of S100B, even as low as ≥0.05 μg/L, beyond 48 h after TBI are strongly correlated to the development of clinically significant secondary radiological findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Corrigan JD, Selassie AW, Orman JA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:72–80.

Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. VI. Indications for intracranial pressure monitoring. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(Suppl 1):S37–44.

Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. VIII. Intracranial pressure thresholds. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(Suppl 1):S55–8.

Chambers IR, Treadwell L, Mendelow AD. The cause and incidence of secondary insults in severely head-injured adults and children. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:424–31.

Graham DI, Ford I, Adams JH, et al. Ischaemic brain damage is still common in fatal non-missile head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:346–50.

Verweij BH, Muizelaar JP, Vinas FC, Peterson PL, Xiong Y, Lee CP. Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:815–20.

Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:4–9.

Marmarou A, Signoretti S, Fatouros PP, Portella G, Aygok GA, Bullock MR. Predominance of cellular edema in traumatic brain swelling in patients with severe head injuries. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:720–30.

Kochanek PM, Berger RP, Bayir H, Wagner AK, Jenkins LW, Clark RS. Biomarkers of primary and evolving damage in traumatic and ischemic brain injury: diagnosis, prognosis, probing mechanisms, and therapeutic decision making. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:135–41.

Slemmer JE, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI. Cell death, glial protein alterations and elevated S-100 beta release in cerebellar cell cultures following mechanically induced trauma. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:563–72.

Oertel M, Schumacher U, McArthur DL, Kastner S, Boker DK. S-100B and NSE: markers of initial impact of subarachnoid haemorrhage and their relation to vasospasm and outcome. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:834–40.

Moritz S, Warnat J, Bele S, Graf BM, Woertgen C. The prognostic value of NSE and S100B from serum and cerebrospinal fluid in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2010;22:21–31.

James ML, Blessing R, Phillips-Bute BG, Bennett E, Laskowitz DT. S100B and brain natriuretic peptide predict functional neurological outcome after intracerebral haemorrhage. Biomarkers. 2009;14:388–94.

Romner B, Ingebrigtsen T, Kongstad P, Borgesen SE. Traumatic brain damage: serum S-100 protein measurements related to neuroradiological findings. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:641–7.

Unden J, Bellner J, Astrand R, Romner B. Serum S100B levels in patients with epidural haematomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:43–5.

Stein DM, Lindell AL, Murdock KR, et al. Use of serum biomarkers to predict cerebral hypoxia after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1140–9.

Buttner T, Weyers S, Postert T, Sprengelmeyer R, Kuhn W. S-100 protein: serum marker of focal brain damage after ischemic territorial MCA infarction. Stroke. 1997;28:1961–5.

Muller K, Townend W, Biasca N, et al. S100B serum level predicts computed tomography findings after minor head injury. J Trauma. 2007;62:1452–6.

Thelin EP, Johannesson L, Nelson D, Bellander BM. S100B is an important outcome predictor in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:519–28.

Jonsson H, Johnsson P, Hoglund P, Alling C, Blomquist S. Elimination of S100B and renal function after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:698–701.

Ghanem G, Loir B, Morandini R, et al. On the release and half-life of S100B protein in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:586–90.

Usui A, Kato K, Abe T, Murase M, Tanaka M, Takeuchi E. S-100ao protein in blood and urine during open-heart surgery. Clin Chem. 1989;35:1942–4.

Kapural M, Krizanac-Bengez L, Barnett G, et al. Serum S-100beta as a possible marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. Brain Res. 2002;940:102–4.

Pelinka LE, Toegel E, Mauritz W, Redl H. Serum S 100 B: a marker of brain damage in traumatic brain injury with and without multiple trauma. Shock. 2003;19:195–200.

Gradisek P, Osredkar J, Korsic M, Kremzar B. Multiple indicators model of long-term mortality in traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2012;26(12):1472–81.

Berger RP, Bazaco MC, Wagner AK, Kochanek PM, Fabio A. Trajectory analysis of serum biomarker concentrations facilitates outcome prediction after pediatric traumatic and hypoxemic brain injury. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:396–405.

Bellander BM, Olafsson IH, Ghatan PH, et al. Secondary insults following traumatic brain injury enhance complement activation in the human brain and release of the tissue damage marker S100B. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011;153:90–100.

Olivecrona M, Rodling-Wahlstrom M, Naredi S, Koskinen LO. S-100B and neuron specific enolase are poor outcome predictors in severe traumatic brain injury treated by an intracranial pressure targeted therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1241–7.

Raabe A, Kopetsch O, Woszczyk A, et al. S-100B protein as a serum marker of secondary neurological complications in neurocritical care patients. Neurol Res. 2004;26:440–5.

Unden J, Astrand R, Waterloo K, et al. Clinical significance of serum S100B levels in neurointensive care. Neurocrit Care. 2007;6:94–9.

Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–4.

Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425–9.

Acker JE, Ali J, Aprahamian C, et al. Advanced trauma life support for doctors—ATLS. 7th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004.

Tong WS, Zheng P, Zeng JS, et al. Prognosis analysis and risk factors related to progressive intracranial haemorrhage in patients with acute traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2012;26:1136–42.

Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4.

Jones PA, Andrews PJ, Midgley S, et al. Measuring the burden of secondary insults in head-injured patients during intensive care. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1994;6:4–14.

Petzold A, Green AJ, Keir G, et al. Role of serum S100B as an early predictor of high intracranial pressure and mortality in brain injury: a pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2705–10.

Signorini DF, Andrews PJ, Jones PA, Wardlaw JM, Miller JD. Adding insult to injury: the prognostic value of early secondary insults for survival after traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:26–31.

Biberthaler P, Linsenmeier U, Pfeifer KJ, et al. Serum S-100B concentration provides additional information for the indication of computed tomography in patients after minor head injury: a prospective multicenter study. Shock. 2006;25:446–53.

McHugh GS, Butcher I, Steyerberg EW, et al. Statistical approaches to the univariate prognostic analysis of the IMPACT database on traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:251–8.

Murray GD, Butcher I, McHugh GS, et al. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:329–37.

Murillo-Cabezas F, Munoz-Sanchez MA, Rincon-Ferrari MD, et al. The prognostic value of the temporal course of S100beta protein in post-acute severe brain injury: a prospective and observational study. Brain Inj. 2010;24:609–19.

Lovell MA, Mudaliar MY, Klineberg PL. Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: complications and difficulties. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:400–5.

Andrews PJ, Piper IR, Dearden NM, Miller JD. Secondary insults during intrahospital transport of head-injured patients. Lancet. 1990;335:327–30.

Gunnarsson T, Hillman J. Clinical usefulness of bedside intracranial morphological monitoring: mobile computerized tomography in the neurosurgery intensive care unit. Report of three cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e5.

Bouvier D, Eisenmann N, Gillart T, et al. Jugular venous and arterial concentrations of serum S100B protein in patients with severe head injury. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2012;70:269–75.

Fazio V, Bhudia SK, Marchi N, Aumayr B, Janigro D. Peripheral detection of S100beta during cardiothoracic surgery: what are we really measuring? Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:46–52; discussion-3.

Unden J, Bellner J, Eneroth M, Alling C, Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Raised serum S100B levels after acute bone fractures without cerebral injury. J Trauma. 2005;58:59–61.

Routsi C, Stamataki E, Nanas S, et al. Increased levels of serum S100B protein in critically ill patients without brain injury. Shock. 2006;26:20–4.

Haimoto H, Hosoda S, Kato K. Differential distribution of immunoreactive S100-alpha and S100-beta proteins in normal nonnervous human tissues. Lab Invest. 1987;57:489–98.

Unden J, Christensson B, Bellner J, Alling C, Romner B. Serum S100B levels in patients with cerebral and extracerebral infectious disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:10–3.

Savola O, Pyhtinen J, Leino TK, Siitonen S, Niemela O, Hillbom M. Effects of head and extracranial injuries on serum protein S100B levels in trauma patients. J Trauma 2004;56:1229–34; discussion 34.

Persson ME, Thelin EP, Bellander BM. Case report: extreme levels of serum S-100B in a patient with chronic subdural hematoma. Front Neurol. 2012;3:170.

Tian HL, Geng Z, Cui YH, et al. Risk factors for posttraumatic cerebral infarction in patients with moderate or severe head trauma. Neurosurg Rev 2008;31:431–6; discussion 6–7.

Robertson CS, Grossman RG, Goodman JC, Narayan RK. The predictive value of cerebral anaerobic metabolism with cerebral infarction after head injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:361–8.

Marshall LF, Gautille T. Large and small “holes” in the brain: reversible or irreversible changes in head injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1990;51:300–1.

Rothfus WE, Goldberg AL, Tabas JH, Deeb ZL. Callosomarginal infarction secondary to transfalcial herniation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8:1073–6.

Marmarou A, Fatouros PP, Barzo P, et al. Contribution of edema and cerebral blood volume to traumatic brain swelling in head-injured patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:183–93.

Raabe A, Seifert V. Fatal secondary increase in serum S-100B protein after severe head injury. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:875–7.

Einav S, Itshayek E, Kark JD, Ovadia H, Weiniger CF, Shoshan Y. Serum S100B levels after meningioma surgery: a comparison of two laboratory assays. BMC Clin Pathol. 2008;8:9.

Smit LH, Korse CM, Bonfrer JM. Comparison of four different assays for determination of serum S-100B. Int J Biol Markers. 2005;20:34–42.

Mussack T, Klauss V, Ruppert V, et al. Rapid measurement of S-100B serum protein levels by Elecsys S100 immunoassay in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting or endarterectomy. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:349–56.

Alber B, Hein R, Garbe C, Caroli U, Luppa PB. Multicenter evaluation of the analytical and clinical performance of the Elecsys S100 immunoassay in patients with malignant melanoma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:557–63.

Muller K, Elverland A, Romner B, et al. Analysis of protein S-100B in serum: a methodological study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:1111–4.

Conflict of interest

Eric P. Thelin, David W. Nelson, and Bo-Michael Bellander declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thelin, E.P., Nelson, D.W. & Bellander, BM. Secondary Peaks of S100B in Serum Relate to Subsequent Radiological Pathology in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurocrit Care 20, 217–229 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-013-9916-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-013-9916-0